Like a nightingale, you sang and then departed

Whenever I feel down, I hum the line, a night bird, you sang and went away; you made my heart tremble (چو مرغ شب خواندی و رفتی) from a song by the renowned Iranian folk singer Sima Bina. Few people know that these lyrics were written by Mohammad-Ibrahim Jafari, a name more commonly associated with the world of painting.

In 1989-1990, I had the privilege of attending two semesters of foundational visual arts courses taught by Mohammad-Ibrahim Jafari, Farshid Maleki, and Hassan Aghili. Their instruction has profoundly influenced my artistic journey.

In 1993, I sought Ebrahim Jafari to be my thesis advisor. I visited the University of Decorative Arts in Tehran and inquired at the university office. They provided me with his class number, and I waited outside the classroom for him to exit, hoping he might recognize me. I greeted him and presented my request; my thesis topic focused on children’s paintings. He asked, “Did you come from Isfahan?” I replied, “Yes.” He responded, “Go see someone named Moareknejad, seek his assistance, and return next week.” My research topic was particularly challenging—a comparison of children’s daily lives with their paintings, especially in Isfahan during that period, which necessitated an exploration of the private lives of Isfahani families.

The following week, I returned to the university and met with Professor Jafari once again. I handed him the proposal papers, which had my name at the top. He glanced at it and exclaimed, “You’re Moareknejad, and you didn’t mention it?!” I replied, “I didn’t have the courage to say it.” He then said, “Now that you’re identified as Moareknejad, I agree. Go ahead and start. When you’ve completed the work, bring it to me—I trust it will be excellent. If you have any questions, feel free to call me at this number.” He provided me with his home phone number, as mobile phones were not common at that time.

In those years, our family did not have a regular telephone, so I would go to my aunt’s house to make phone calls. From time to time, I would call Jafari to provide updates on my work. Occasionally, he was not home, and I would inquire about his whereabouts. I would go through various numbers, searching for him at relatives’ homes, and somehow manage to track him down. He would laugh and say, “It’s interesting that you even have my relatives’ phone numbers!”

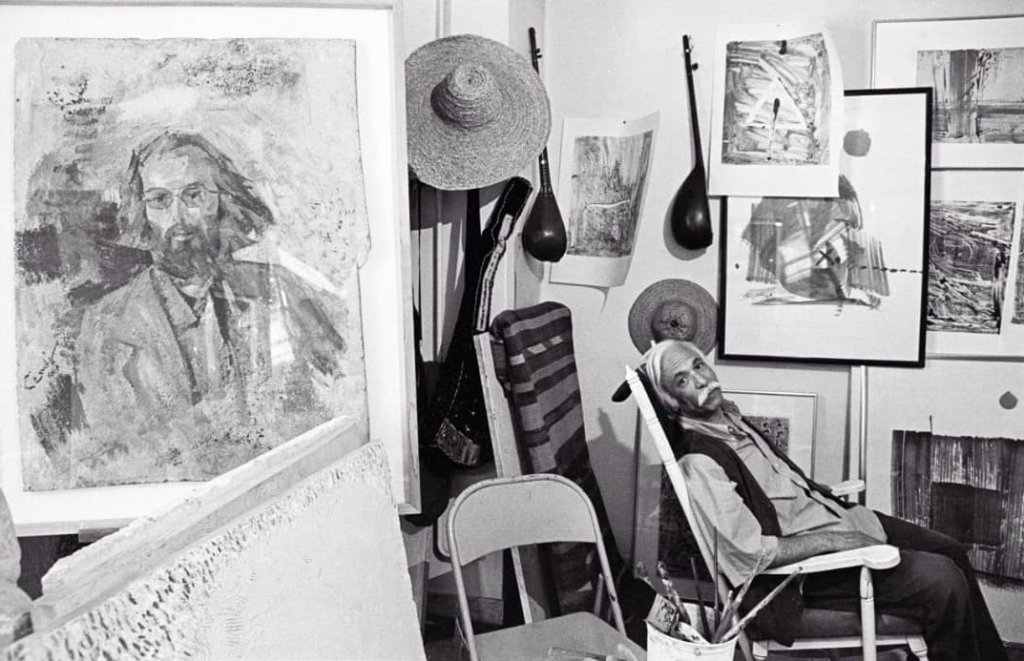

I also visited his studio a couple of times; it was located on the second floor of his home. Inside, there were several pigeons, along with a few flowers and plants housed in large glass jars. He often brought out books about various artists for me to examine, explaining their artistic perspectives and how they interacted with their surroundings. One foreign artist he introduced to me had created something particularly intriguing: he painted scenes from an aerial viewpoint, envisioning the spaces he observed from ground level within his field of vision. On one occasion, his daughter, Sara, was present as well; she was preparing to take the entrance exam for art university.

The thesis took approximately two years to complete. To achieve satisfactory results, I taught in various locations, distributed questionnaires, visited homes with the families’ permission, listened to their stories and concerns, and ultimately completed the thesis.

In 1995, I was in a hurry because I had been accepted into a master’s program in art but was lacking the necessary grade for my thesis. I called Ebrahim Jafari, who instructed me to come to his house in the morning. That same day, I packed a dozen or so collage-style paintings, each approximately 70 by 50 cm in size, along with my thesis under my arm, and took the bus to Tehran, arriving at his house early in the morning—around 7 a.m. I was directed to his studio on the upper floor of his home while he prepared for our meeting. After waiting for a short while in the studio, they arrived. From there, they contacted Hossein-Ali Zabehi, saying, “We’re heading your way now, so be ready so we don’t waste time and can go see Iraj Zand.” They then called Iraj Zand (Iraj Karim Khan Zand: 1930-2006), who replied, “We’ll be with you in an hour.” Iraj Zand’s studio was likely located on one of the streets around Revolution Square, probably in the northern part. I got into Professor Jafari’s car, and during the drive, I mentioned my interest in working with video art. He responded, “That’s great; Abbas Kiarostami also began filmmaking at your age.”

On the way, Zabehi joined us, and we went straight to Iraj Zand’s studio. We climbed a few stairs to reach a series of interconnected rooms. We sat on a chair in one room. I laid out my paintings on the floor and gave each of them a copy of my thesis; I spent an hour explaining. There were numerous questions, and I answered them all. Perhaps in a regular thesis defense, I would not have been so scrutinized, but it was a bit tough; nonetheless, I answered everything they asked.

In the corners of the room, handwritten notes were clipped to nails on the wall. Jafari asked Iraj Zand to read a few of them. Zand read some pages; most were their thoughts and views on art, written in just two or three lines. I wish he had lived longer to publish those writings. Zand had only recently found his personal style in art before his death and was sculpting with metal surfaces.

After the thesis defense and the explanations, they turned to my paintings, which I had laid out on the floor. They looked at my work, and Jafari said, “The colors and textures are very Isfahani.” I found this comment from Jafari quite interesting. The review and discussion of my work lasted until almost noon—around 1 p.m. We had a cup of coffee during the process. The thesis defense was finally over. They recorded the grade on the official thesis evaluation sheet: “20 with distinction,” and signed it. I had not expected that. I took the paper, said goodbye to the professors, and headed straight to the bus terminal—probably the one in South Tehran—to return to Isfahan.

I was in a hurry and needed to get my thesis grade quickly to enroll in the master’s program. The next morning, I took my thesis and grade sheet to the head of the art department, Dr. Ashouri, who was the dean of the Isfahan Art School at the time—back then, the Isfahan Art School was under the supervision of the Tehran University of Decorative Arts. The school was housed in an old building on standard Street (Tohidkhaneh). I walked through the hallway into the courtyard and entered one room on the right, where Dr. Ashouri was sitting at his desk with his back to the courtyard window. I greeted him and handed him my thesis and the grade sheet. He looked at the sheet and said, “Jafari always gives high grades like this.” There was disdain in his words! Then he wrote a grade on the sheet: fourteen! It felt like a bucket of cold water had been poured over my head—I was deflated. He signed the sheet and handed it back to me, then stood up from his chair. Dr. Ashouri tucked my thesis under his arm. I said, “You didn’t even open it and gave a grade without looking at it.” He replied, “I’ll read it later.” The sheet was in my hand, and out of anger, I snatched the thesis from under his arm and stormed out of his office.

Every memory brings another memory in its wake, but that’s okay.

A while later, one of Dr. Ashouri’s colleagues, who was also a professor at the University of Arts, caused trouble for Dr. Ashouri. Dr. Ashouri’s friend reported to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance that the library books were not in line with academic standards and were uncensored. Consequently, they came to the art library and took away many of the foreign books. The books that were left behind had their nude images blacked out with marker pens. Dr. Ashouri was removed from the Faculty of Arts and was forced to move to Tehran to work in the administrative department of the University of Decorative Arts. And that same colleague took his place.

I submitted the grade sheet to the Azad University of Isfahan (Khorasgan), and they issued a temporary graduation certificate, instructing me to go register for the master’s program. I went to Tehran, but I could not register because that certificate did not have legal validity, as the President of Azad University Khorasgan, Dr. Foroughi, had taken no steps to validate the painting program. I returned to Isfahan, and it was decided that I would be introduced to Azad University Tehran to be referred to one of its affiliated universities and complete my graduation process.

A new letter was sent from Isfahan stating that, since I was the top student—something I had just realized myself—and had been accepted into the master’s program, they requested that I be referred to one of the central offices of the Azad University in Tehran to obtain my degree. I went to the central university; I contacted the secretariat and, after several weeks of constantly traveling between Tehran and Isfahan—one day in Tehran and two days in Isfahan—I had to get a recommendation letter from Dr. Foroughi for Dr. Jassbi. There was no direct access to Dr. Jassbi’s office, so I waited by the university entrance and, when he finally left, I stopped his car and handed the letter to him through the lowered window. The next day, I was referred to the Azad University Central Office in Tehran, Palestine Street. These back-and-forth trips and referrals continued for several months, extending from October to December.

At the Azad University Central Office, I was told I needed to speak with the management, which was headed by someone named Shokriz or something similar. The office hours were uncertain, and for several days, I loitered outside the university office, waiting for the manager to show up. Eventually, I was told the manager would arrive that evening. I waited in the street until around 4 a.m. when the manager finally appeared with two bodyguards. I approached, but the bodyguards pushed me away. Seeing my persistence, the manager eventually let me into his office. I briefly explained the situation, and he said, “A letter was shoved up your backside, and you’ve been sent here; what can I do?!” He was more of a goon than a university manager. He called the bodyguards, who escorted me out. That year, I lost the opportunity for a government master’s program.

After a year of being barred from the entrance exam, I reattempted the master’s entrance exam in 1997 and was accepted. My persistence paid off, and finally, the Azad University in Tehran agreed to issue my bachelor’s degree in painting. The president of Azad University in Khorasgan, Dr. Forooghi, managed to influence the Tehran branch. Dr. Forooghi told me, “We’re sending your file along with all the files of painting students to Tehran. Either they will accept all of them or reject all of them.” Dr. Forooghi sent all the files to Tehran through one of the painting students, and they ended up accepting all of them!

Finally, in the summer of 1997, after a year and a half of hard work, I managed to obtain my valid and legal graduation certificate from the Tehran Central Branch of Azad University. Thanks to this, all my friends also received their bachelor’s degrees, and we all became graduates of Tehran University Central. A piece of cardboard, 20 by 30 cm, was our entire credential! With that piece of cardboard, I enrolled in the master’s program in Art Research at Tehran University. After registering, the university invited students to the “House of Arts” to attend a lecture by Nader Ebrahimi, the author of “Fire Without Smoke.” Ebrahimi spoke about Sadegh Hedayat and discussed how to make money from writing. Somehow the conversation shifted to Hedayat, and he remarked, “Sadegh Hedayat had neither sincerity nor was he a guide.”!!! (The name “Sadegh Hedayat” literally means “truthful guide.” )

With the start of the university classes, my questions began, causing quite a bit of trouble. Ultimately, I couldn’t last more than ten days, withdrew from the program, and spent another year waiting. In 1999, I took the entrance exam again and was accepted into the Painting program at Tarbiat Modares University.

In 1989, the Khorasgan branch of Azad University in Isfahan, under the management of Dr. Foroughi, began admitting students in the field of painting. However, this initiative did not continue. Nevertheless, those students brought about a transformation in the art scene, especially in painting, revitalizing the city’s artistic environment, and its impact is still felt today. Unfortunately, because of Dr. Foroughi’s stubbornness, the painting program at Azad University Khorasgan was discontinued.

I was happy that the efforts of those few years paid off in honor of my dear professor, Mohammad Ebrahim Jafari.

Rasoul MoarekNejad

2020