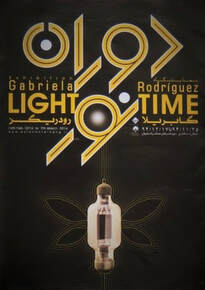

RESILIENCE OR LIGHT TIM

Gabriela Rodríguez Penagos

Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Isfahan

Isfahan, Iran

Febrero 14 – Marzo 7, 2016

Raoul Moareknejad

They range from small objects, volumes, sculptures, artifacts — items that are both not unfamiliar and sometimes nostalgically well ingrained in the Iranian psyche. They are familiar because a considerable corpus of volumetric works due to rituals haunts the Iranian historical and visual memory and these works are still in use for various ceremonies. On the other hand, for the past half-century, people have seen such works in the field of contemporary art history. Sculptors have used reused and discarded stuff to make art works including Jaza Tabatabai, who have transformed objects into sculptures that contain symbolic, archaic, and mysterious qualities for the observer.

Within that context, the work of the Mexican artist Gabriela Rodríguez Penagos speaks to Iranian sensibility in art. Another shared thread between Rodríguez’s work and Iranian art —even with important differences in their modes of expression — is the relationship to the written word, a long-held tradition in Iranian art. Literary-inspired and textual works include everything from Shahnameh illustrations to modern works, such as pieces by Parviz Tanavoli, including a work titled “Farhad the Stone-Cutter.”

Thus, what the majority of Iranian artworks denotes is the object itself under its material context, which breaks the iconic transcendence. Essentially by combining disparate objects to form a singular piece, they echo the Platonic cave theory of representation; this piece itself is an object in direct relation to a transcendent whole that is rooting somewhere outside of itself and is only existing as an inking of the real, a bleak representation. But the difference between Iranian artworks and their audience, and Rodríguez’s works and their audience, is the different existential paradigms they engender.

This process allows the transposition of things that happen from one layer of meaning to another, adjusting the surfaces of existing things to their place in their world. And just like electric lamps that have remained in the shadows, accumulating dust for years, products that the artist has turned into new and original concepts and showcased in the museum or galleries This is a displacement from deep obscurity into the foreground of a new thing. Crucially, this change and transposition is important in that 1) the new object being encountered is other to the previous one (and recognized as such by an audience) and thus something new and separate, and 2), the new form actualizes a new idea that replaces and stands in for the symbolic encodings of the brain, thought, and the human mind.

Intertextually, these works operate via intercultural and inter-significational discourse.

*Interculturality is impressive in the displacement of Mexican culture towards our culture (Iranian-Isfahani). The tendency of Iranian culture, especially that of Isfahan, to receive foreign influences and sometimes even prioritize those influences over its own traditions, is well-known in history.

Through this cultural exchange, artwork might be viewed and understood from a completely different perspective in another culture than the one it originally came from. We cannot do anything about it; the same work in two cultures yields different intensities of meaning.

The written texts also engage in intertextuality as they relate to the sculptures. Somehow these two modes of artistic expression are interplaying to produce a third entity. The collaboration of Gabriela Rodríguez Penagos (visual artist) and Sergio de Regules (literary artist) contributes to set this intertextual bond.

This is especially relevant considering that the written texts are bilingual. Both texts either written in different languages — English and Persian — have an intercultural element. Through no fault of their own, these are texts that invite the reader to play with the wording.

“Their object-ness is also evident in the inter-significational relationship between the works. These objects were repurposed from their original functions as artistic volumes. The lamps have achieved permanence (their new appearance) after having been taken out of their historical context.

Conventional electric lamps are neutral objects in and of themselves, but they have implicit meaning enshrined in their very nature. They are neutral in that they do not decay over time, they manifest the notion of eternity. With this object the artist aims at something general, universal and transcultural: light.

Light is an archetype and that meaning differs from one culture to another. As such, for an Iranian viewer, the idea of “light” carries multitudes of associations. It is ingrained into Iranian culture, seen in paintings, where light spills out of the entire canvas, and traditional religious architectural spaces. Such halos of light around religious figures symbolize divine selection and the purity of innocence, which Christ illustrated. Light also represents truth, as seen in Icarus’s fateful attempt to fly to the sun. The division of the soul is a common theme in the panorama of Persian literature, including in Attar’s “Mantiq al-Tair” and Ayn al-Qudat Hamadani’s philosophical consideration of black light.

Electric lamps used to display pictures and sounds, but also there were once enough light to shine something close to the truth. Today, though, they’re devoid of content, becoming sculptures in their own right. They have been divested of light and image in order to take on a new form, that of the Medusa’s gaze that enchanted television viewers. Now, the lamps themselves are enchanted, like the monstrous figures of Aztec mythology that turned to stone with the first light of dawn.

The terror of the image that whipped through every late modern and mid- postmodern life, visiting every house, has been replaced by a silent image that has taken on another shape, and symbolic form. The lamps with images decaying lamps have turned into darkness in their fluttering wings blood and revealing the truth of the eye.

Title: The Mind

The Mind:

We should understand that thought comes from another dimension of the mind. It is this kind of thought that produces darkness and light in human consciousness. The mind can create different connections with other people. Such connections may occur in words, expressions, forms or even a gaze that leaves the imprint in the mind of another.

The sculpture lives in a cube. The inside of the cube is bright green and the outside is dark. This cube represents thought, reason, perfection and the masculine principle. It is the most complete form in the universe, according to traditional philosophers. Like the Kaaba, the ancient Egyptians carved statues of pharaohs from cubic stones. The blackness of the cube represents a return to totality, the world beyond the earthly, the infinite and profound world that can also be terrifying. By contrast, the interior is a bright green as sparse as the human sphere. Everything that a human can think, the color green; everything beyond humanity, in dark (and barren) ground.

The cube is open on front and back allowing to access the face and back of the head, while being closed on the other sides. This design represents the concept that humans experience more through sight than through hearing. Simultaneously, the words they speak attune them to the melodic harmony of green sound found within the cube, a manifestation of their innermost selves.

Its sculptural form is earth-toned and has a clay-like texture. It looks down, as if it has seen everything. Its lips are sealed, silent, meditating on another realm. This introspection has brought a lush green to its surroundings.

If we take a look at the back of the sculpture, we can see a lamp. It is a lamp that seems to provide all of the thought, reflection, and imagery of the sculpture, residing in its head. And the lamp is modifying the significance and negating some of the meaning expressed by the front of the face, which looks mechanical. It is no longer just a thought but becomes mechanical and somehow obedient. On the lamp, in a color that pops against the green, is the name of its manufacturer and place of origin, revealing that part of the sculpture’s conceptualization comes from elsewhere.

And yet, the sculpture’s face welcomes such an idea, with an expression that depicts a soothing demeanor that brings peace to the viewer. In summary, the reflection, serenity, and meditation are contained in a container that is on top of the head. The ship is made of the same electric devices. The head is there, in vanitas still life the head is generally severed and presented in front of the viewer thus, all the organs have no function, as the head is the most important part. Ideally, it is creating the world around it, and we hope that it is nurturing good thoughts for a better world.